Remember the 1990s? It was a heady time for investors.

Stocks surged to unprecedented heights as excitement about the internet’s promise captured the world’s imagination. It was an era of “hot initial public offerings (IPOs)” featuring unprofitable companies like Pets.com.

These companies went public based on hype, hope and “new-era” metrics like eyeballs. And investors couldn’t get enough of them.

The dot-com bubble was truly a mania. It seemed like everyone in America was trading stocks and bragging about their winnings.

And a few key factors suggest we are a long way from those days…

Stock valuations: Today’s price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios are higher than average, and the so-called Shiller P/E (or CAPE ratio) hasn’t been this high since 1999. But the 10-year Treasury yield was close to 6% in 1999, while it sits under 2% today.

In other words, stocks offer better value than bonds at current levels. As a result, institutional investors are willing to pay more for corporate earnings. The end result is “multiple expansion,” or higher-than-average P/Es.

Inflows into equity mutual funds: “Even with a roughly 30% rise in the U.S. stock market, investors poured a record amount of new cash into taxable bond funds in 2019, and U.S. stock funds saw net outflows” of more than $41 billion, Morningstar reports.

The opposite occurred in 1999 as investors rushed headlong into U.S. equity funds, particularly tech funds.

Sentiment: There’s widespread disbelief in this market. Investors are not wildly bullish on stocks. Otherwise, they would be putting money into equity funds rather than taking it out.

Additionally, the failure of WeWork’s IPO last year and the skepticism around Casper’s initial efforts to go public demonstrate the stark difference between today’s market and 1999.

Those factors tell you it’s just not like it was back in the go-go days of the dot-com bubble.

But let’s go further back in time, to the mid-1990s. History might not repeat, but it often rhymes…

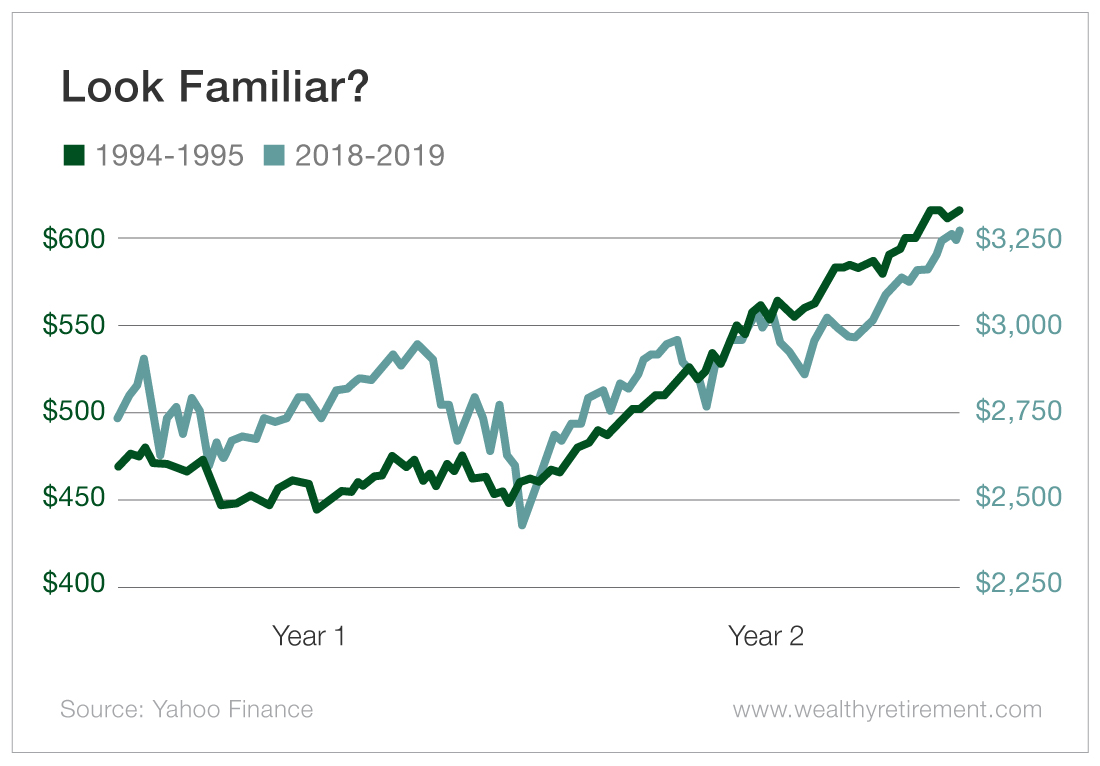

In fact, today’s environment has more similarities to the heady 1994 to 1996 era stock market than you might expect – and certainly more similarities than it has to the market peak of 1999 to 2000.

- In 1994, the market struggled as the Fed was in the midst of a tightening cycle. The market surged 32% in 1995 after the Fed started easing. A similar dynamic occurred in 2018 and 2019.

- The market also struggled in 1994 because of rising trade tensions between the U.S. and Japan, the latter then the world’s second-largest economy. In early 1995, President Clinton threatened 100% tariffs on certain Japanese cars.The market was on tenterhooks until the U.S.-Japan trade dispute was resolved in June 1995.

- Like President Trump, President Clinton faced partisan investigations back then – and eventually impeachment.

- During the mid-1990s, the U.S. economy was the world’s strongest, while the global economy struggled.

- Large cap stocks outperformed small cap ones, and U.S. stocks outperformed international ones during this era.

That said, it wasn’t all smooth sailing. Stocks got hit by a series of shocks between 1996 and 1998, most notably the Thai baht crisis, Alan Greenspan’s infamous “irrational exuberance” speech, Russia’s debt default and the blowup of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund.

Yet despite these periodic setbacks, the market marched steadily higher in 1997, 1998 and 1999. Notably, Greenspan learned the lesson from his “irrational exuberance” comment and became the market’s biggest supporter after 1996. Then, as now, the Fed’s easy money policies helped the stock market hit record highs.

The Fed’s “pivot” last year was more than just a change from raising to cutting rates. Last year marked a generational shift in the Fed’s focus. Under Jerome Powell, it is now more concerned about deflation than inflation.

“Based on what the Fed has said, you know they’re not going to raise rates,” Tony Dwyer, Canaccord Genuity’s chief market strategist, says in the latest episode of my podcast. “They’re not going tighten policy. That’s why valuations are going up.”

How much higher valuations go remains to be seen. But if the parallels to the mid-’90s continue to play out, the market is going a lot higher before the music stops. It will eventually stop, of course – just like it did in 2000.

But the worst mistake investors can make is to think “this will end badly,” according to Dwyer. “Because as soon as you say that, you’re going to invest too defensively.”

Investors should remember that market déjà vu is not always a bad omen. Take advantage of this familiar atmosphere by using any market setbacks to add exposure to economically sensitive industries like financials, industrials and technology.

If you’re going to relive the past, you might as well profit from it.

Good investing,

Aaron