“I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship,” said IBM to the software company Red Hat this summer as the two closed their “landmark acquisition.”

Or wait – that was Rick Blaine to Captain Louis Renault in the 1942 film Casablanca.

But the sentiment remains the same…

Mergers and acquisitions are unique events in that they rarely occur more than once in the life span of a company.

When they do occur, they’re often catalysts for skyrocketing share prices.

Several of our readers have even witnessed this firsthand.

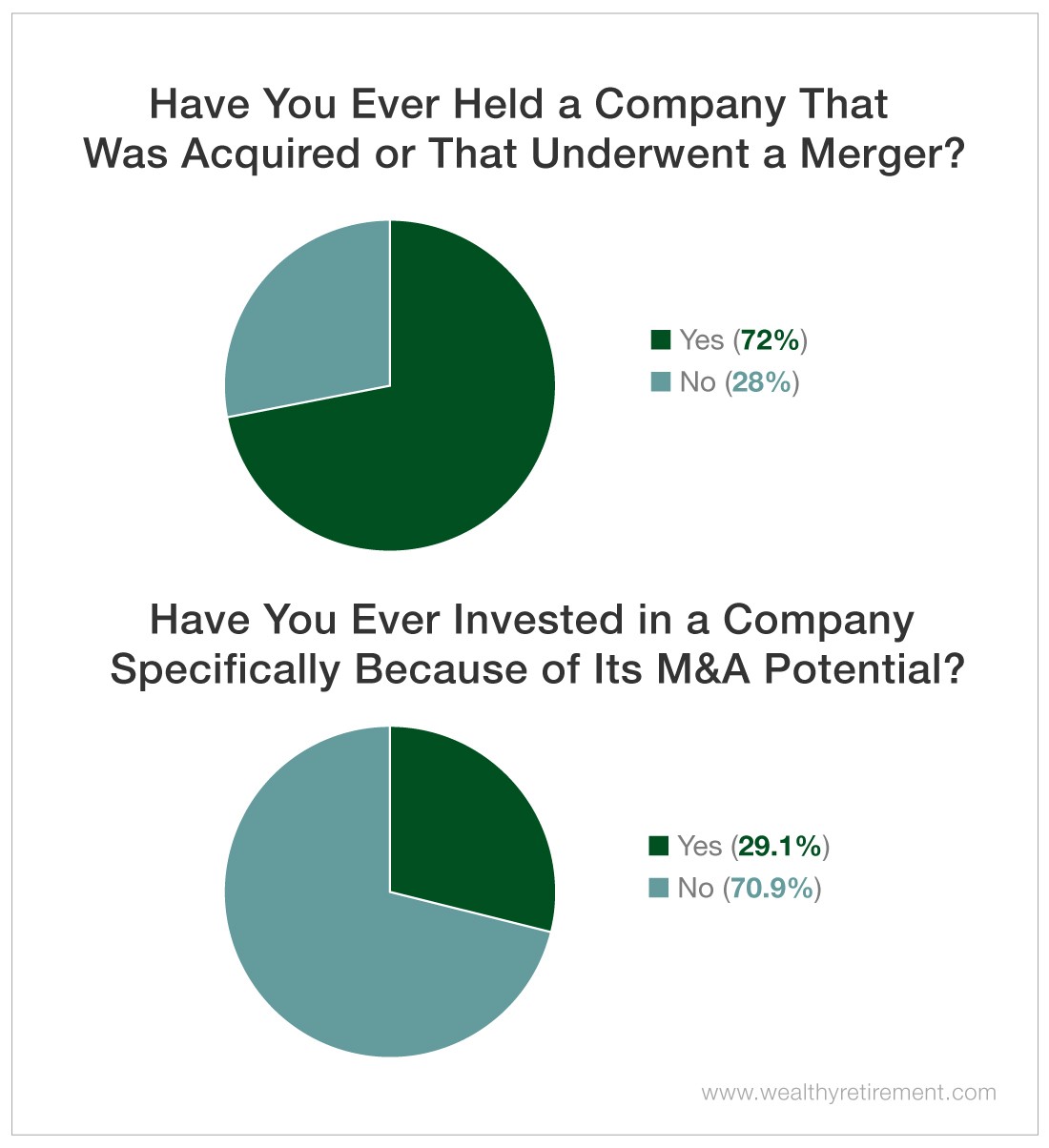

As many as 72% of respondents to our latest survey indicated that they have held a company that was acquired or that merged with another company.

In fact, more than one-quarter of our respondents choose investments specifically for their potential to undergo mergers and acquisitions, also known as M&A activity.

This activity is especially common in the biotech sector.

Here, emerging companies with transformative technology are often scooped up by large cap players that recognize their potential.

But as we witnessed last summer, the phenomenon isn’t limited to biotech. Even tried-and-true dividend champions like IBM spice things up from time to time to meet their businesses’ goals.

(And Red Hat’s 49% one-day leap following the acquisition announcement should be evidence enough of investors’ feelings about the deal.)

However, the potential of M&A activity extends beyond this “early alert system” for dramatic leaps…

Deal or No Deal?

It’s possible that the frequency and scope of these deals could also serve as indicators for the health of the market.

Imagine this: You hold a position among the upper-level management of Authentic Brands Group, a company that owns a variety of clothing brands, including Nine West.

Authentic Brands is one of the current bidders in the battle to acquire the beleaguered Barneys New York, which declared bankruptcy late this past summer.

The offer? It was $264 million.

“A.B.G. is essentially betting that the future of retail lies with the abstract values of brand names rather than in-person shopping experiences,” write Vanessa Friedman and Sapna Maheshwari in The New York Times.

It’s an expensive bet.

With fears of recession looming, companies that consider acquisitions have to put their cards on the table.

Considering our example, put yourself in their shoes…

Do you tie up your cash in high-potential ventures?

Or do you hold on and brace for the blow of a market sell-off?

Regardless of their choices, these companies’ managements’ actions speak louder than their words.

Mergers and Acquisitions as a Market Indicator

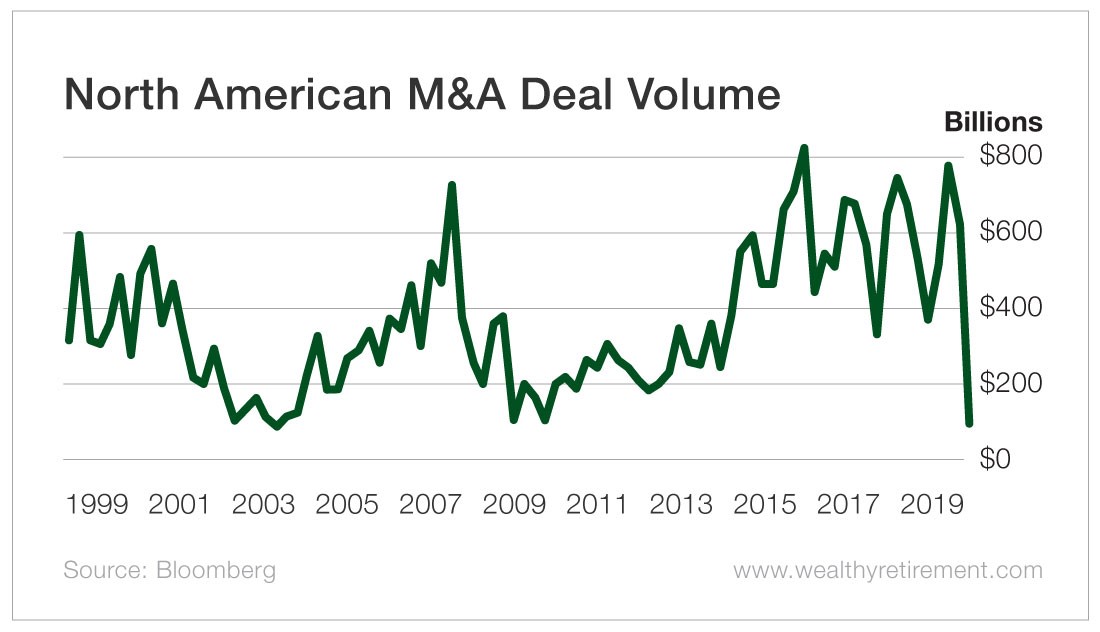

Consider the following chart for example.

You’ll notice that, right now, deal volume is extremely low.

Deal volume is a function of the number of mergers and acquisitions (deal count) and their average value (premium) at a given time.

Note that as recession loomed at the sunset of the dot-com boom, and again in 2007, M&A deal volume fell dramatically.

Earlier this year, we celebrated a decade-long bull market – making it the longest bull market in U.S. history.

As the markets get more volatile, it’s no wonder that companies are beginning to take a hot-and-cold approach.

Furthermore, news triggers, like the tensions between the U.S. and China, can lead to skittish markets.

All the same, the steep drop in M&A volume in 2019 bears watching.

Whether the cause is damaging or benign, the parallels to 2000 and 2007 are clear.

Therefore, while you watch for M&A activity as a way to get in early on the market’s best opportunities…

And while you celebrate when your holdings post dramatic one-day leaps…

Also consider what it suggests when all is quiet in the market for mergers and acquisitions.

After all, like in a game of rummy, no company wants to get caught with its hands full when the dealing stops.

Good investing,

Mable