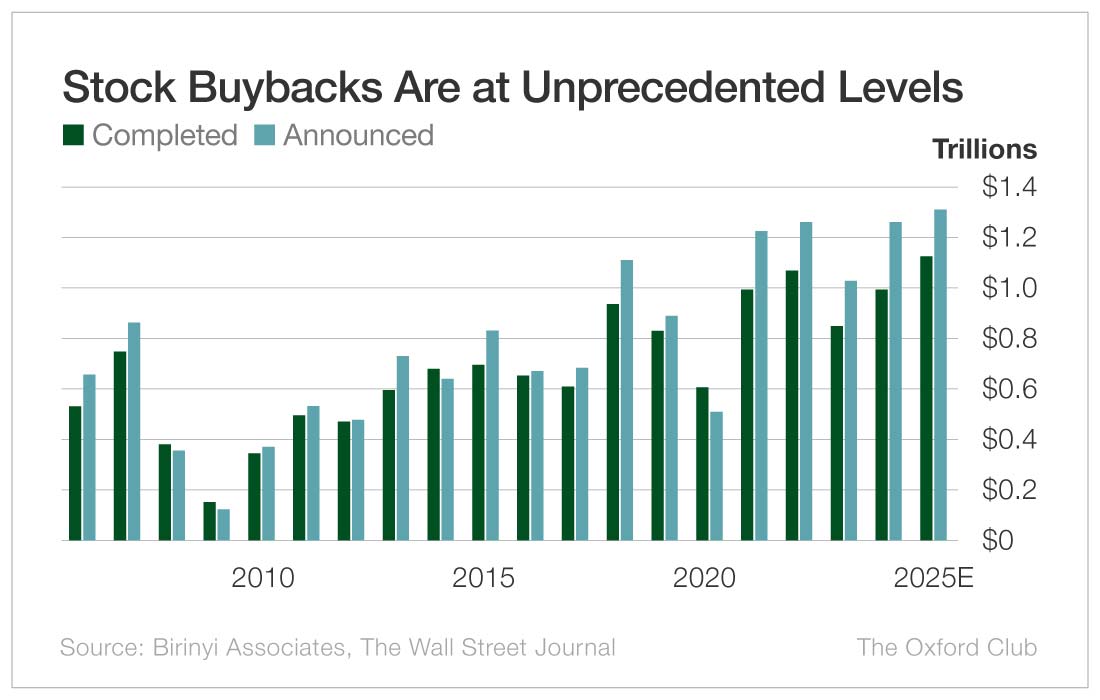

In 2025, U.S. companies are expected to buy back $1.1 trillion worth of stock. (That’s equal to the size of the entire economy of Turkey, the 18th-largest in the world.) Companies have already announced $984 billion worth of buyback authorizations. Both are record numbers.

By the end of 2025, companies are expected to have announced over $1.3 trillion in buybacks.

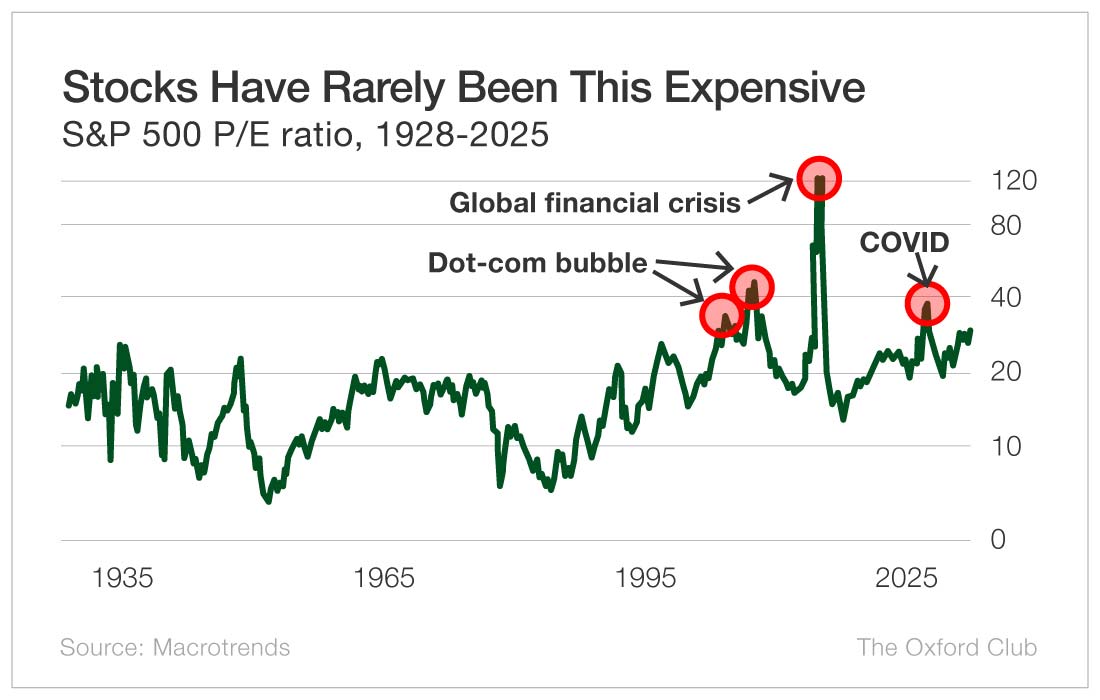

This is happening at a time when markets are at all-time highs and price-to-earnings, or P/E, ratios are very extended. In fact, the market’s P/E ratio is the highest it’s been except for during market anomalies like the COVID pandemic, the global financial crisis, and the dot-com bubble.

I don’t believe that the P/E ratio is the definitive measure of a market’s valuation or its likely direction. But it’s a useful indicator of how frothy a market is, and it doesn’t make sense for companies to be snapping up shares at these prices just because they have the money.

Instead, they should buy back shares when markets tank, but they almost never do.

I have three main arguments against buybacks.

1. Let me decide what to do with the extra cash.

Buybacks are considered a method of returning cash to shareholders. If a company has cash that it wants to return to shareholders, then I want to decide whether the stock is a good value. I don’t trust a CEO who may be incentivized to manipulate the numbers in order to boost earnings per share.

Here’s what I mean.

Let’s say a company earns $100 million and has 100 million shares outstanding. That means it earns $1 per share.

The company buys back 10 million shares.

The following year, earnings are flat and it again makes $100 million in profit. But now there are only 90 million shares, so earnings per share are now $1.11 – showing 11% growth even though the company didn’t make any more money.

2. Companies buy back shares at the wrong time.

In my book Get Rich with Dividends, I cite a study by Azi Ben-Rephael, Jacob Oded, and Avi Wohl that was published in Review of Finance that found that small companies often buy back shares at depressed levels, but large companies do not, because they’re “more interested in the disbursement of free cash.”

In other words, management teams of large companies are more concerned with showing the public that they’re doing something with the excess cash rather than being good stewards of capital.

3. Management teams are often hypocrites.

Executives are happy to buy back shares at high prices with your money while they’re selling their own shares.

The three largest announced buybacks this year are from Apple (Nasdaq: AAPL), Alphabet (Nasdaq: GOOG), and JPMorgan Chase (NYSE: JPM).

There have been no insider buys at Apple in a decade. Meanwhile, on August 8, Apple’s senior vice president of retail and people, Deirdre O’Brien, sold $7.8 million worth of stock. Last year, she sold $23 million worth.

Chris Kondo, the principal accounting officer, sold $934,000 worth in May – and that’s on top of the $5 million that he sold last year.

And this year, CEO Tim Cook has sold more than $24 million worth of stock.

So Cook and friends are cashing in while using shareholder money to repurchase up to $100 billion in shares.

Does that pass the smell test?

Same story at JPMorgan Chase. No insider buying since 2023, but a whole lot of selling, including by CEO Jamie Dimon, who has sold more than $170 million worth of stock this year.

Yet the company authorized a new $50 billion stock repurchase plan last month.

You see the pattern.

Insiders sell for lots of valid reasons. They may be diversifying their portfolios, estate planning, paying for a wedding, etc. But should they be allowed to sell their shares, collecting millions of dollars, while using your money to support the stock?

If a management team stands by its repurchase decision, how about all the insiders commit to not selling any shares for a year?

I trust management to run the business. I don’t trust them to make the right decisions with excess cash unless they’re also buying shares themselves.

When a company has too much cash, it should pay shareholders a special dividend or boost the regular dividend. We are all better off making our own decisions on what to do with the money, rather than having a management team with conflicts of interest make the decision for us.

I disagree. I think it’s a great idea for companies to buy back shares when they have excess cash and don’t have good investment opportunities. It increases value per share, and I would rather have deferred capital gains than immediate taxable income.

Très pertinent et éclairant. D’accord avec Marc.

“If a management team stands by its repurchase decision, how about all the insiders commit to not selling any shares for a year?”, well, I’ve never thought this way, thanks for that.

I agree. I special dividend would be nice. I read your book; it was excellent. I often wondered that these companies that have been around forever might be undoing all the stock splits of years gone by, but I definitely agree insiders should not be selling while the company buys back shares.

Marc keep doing your thing, because your updates are dead on the money…”You are different” meaning NO ONE IS LIKE YOU with the up dates what to do… Thumbs up!

Very nice insight Mark.

Thank you for enlightening me. And yes, I agree!

Old Blue

Marc that is one way to look at. Another it these “seller” are getting a very large amount of stock as part of their compensation in the form of stock options. It’s prudent to not put “ all your eggs” in one basket. When you show the numbers show what percent of total holding are being sold instead of dollars.

Marc, I couldn’t agree with you more. These Corporate execs operate in their own self-interests.

Good point. I always thought that this helped the shareholders.

Right on Mark! While we have laws against inside trading, the politicians and corporate management cannot help themselves from taking advantage of their lofty positions. They need it the least, but they rush to yet another big payday on the backs of their shareholders. Shame on them, the greed bastards!

I agree that a special dividend should be paid. The company can give a small uptick in the regular dividend and with the excess a special dividend.