It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, it’s magical.

You check on your portfolio in the morning, and one of your stocks is up 25%, 40% or 60% – in ONE DAY!

When a stock jumps that much in the opening minutes of trading, 9 times out of 10 it’s because the underlying company is getting acquired. The acquiring company typically pays a premium in order to get shareholders of the other company to go along with the deal.

For example, let’s say Company A is trading at $20. Company B makes an offer to acquire Company A for $28.

It pays $8 more than the current price because in order to make the deal appealing for shareholders and management, the price needs to be considerably higher than it is today. After all, if the price is just slightly higher, say $21, there will not be much motivation for management and shareholders to sell.

In an average stock market, Company A’s stock would likely climb above $21 within the year – so Company B needs to provide some incentive for everyone to sell. A 40% premium could do the trick.

Shareholders of Company A won’t get the $28 immediately. Usually, the stock of the company getting acquired shoots higher, but not all the way to the offer price. That’s because there is some risk that the deal won’t go through.

That could be because government regulators won’t allow it, shareholders may vote it down or a host of other reasons. So the stock may jump to $27, and as the weeks go by, it might slowly climb up toward $28. If the deal is consummated, shareholders will receive the full $28 per share.

Keep in mind, $28 isn’t automatically the final price. Upon receiving the $28 offer, Company A could say, “Thanks, but no thanks.” When that occurs, Company B usually sweetens the deal, in this case, maybe offering $30.

In this scenario, upon seeing that Company A is for sale, Company C makes an even better offer at $33. Finally, Company B makes one last offer at $34, which is accepted.

Shareholders would see a pop in the stock when the first offer was announced, a second move higher when the offer was raised, another spike when Company C got into the mix and then one last increase when the $34 offer came in. An initial 40% premium got raised to 70%, and the stock climbed along with each new development.

This doesn’t happen all the time, or even most of the time, but it does occur. More often, just a simple offer is made, the stock jumps, and shareholders either cash out fairly quickly or wait for the deal to be completed to get the full amount.

Here are some recent examples.

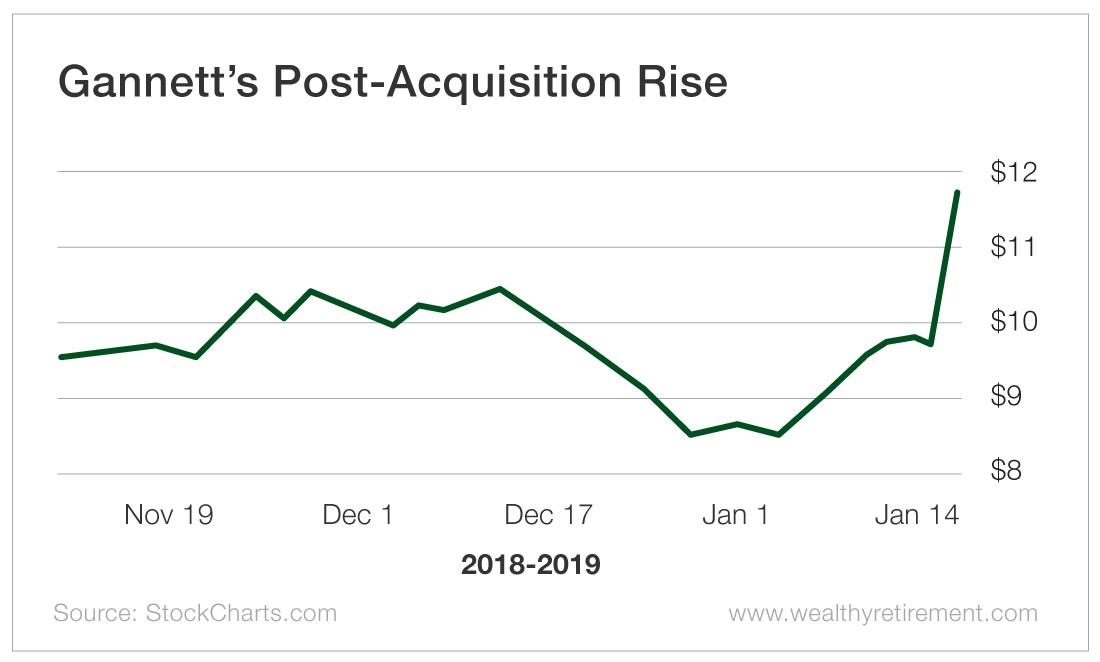

On January 11, newspaper giant Gannett (NYSE: GCI) closed at $9.75. Over the weekend, it received an offer to be acquired for $12 by Digital First Media. On Monday, January 14, the stock opened at $11.56 and closed at $11.82, a 23% gain in one day.

On Friday, February 1, Ellie Mae (NYSE: ELLI) closed at $76.43. Later that day, a story broke that the company had retained an investment banker to explore a sale. On Monday, the stock closed at $83.99, a 10% one-day pop.

Then, last week on February 12, the company agreed to be acquired by a private equity firm for $99. It closed at $98.95, a 29% gain in less than two weeks.

In October of last year, IBM (NYSE: IBM) said it would buy Red Hat (NYSE: RHT) for $190 per share. Before the deal was announced, Red Hat closed at $116.68. The next trading day, it opened at $174.16, 49% higher than the prior close. Investors who hang on until the deal is completed will receive a 63% premium to the close the day before the announcement.

It’s incredibly exciting when you hold a stock in a company that gets bought out because it is usually a windfall for investors. Next week, I’ll discuss some of the ways you can increase your odds of owning a company that is likely to get acquired.

Good investing,

Marc